On Randomness in (Social) Science

Posted on 06/12/2014 by Jakub Langr

Posted in technical

A while back I was mentioning how I was confused by the randomness as an emergent property of human systems, and so I have been giving this some thought, which I thought I might share with the world. The underlying problem always has been why is emergent randomness a good model of human behavior. At some level, we understand that our actions are deterministic at least on above-quantum level and I really dare not make any statements about the quantum nature of the universe.

Before I start the discussion it is worth pointing out that I will try to make this as intuitive as possible, but some math will have to be involved, though I tried to make it so that it is not necessary to understand everything to really understand the point of this article. It was included to make the reasoning a bit easier. At the same time I am making some imprecise statements for the sake of understanding, but if you feel I might be leading people astray, feel free to drop me a line.

The very definition of randomness is lack of predictability. That seems almost circular, but first thing to note here is that does not mean that all outcomes are equally likely. Think about a pair of dice, and our random variable ("what we measure") as the sum of the two rolls. Here there are seven has six possible combinations (6+1,5+2,3+4,4+3,2+5,1+6), giving us approximately normal distribution centered at seven:

COUNT NUMBER OF PROBABILITY

COMBINATIONS

2 1 2.78%

3 2 5.56%

4 3 8.33%

5 4 11.11%

6 5 13.89%

7 6 16.67%

8 5 13.89%

9 4 11.11%

10 3 8.33%

11 2 5.56%

12 1 2.78%

Total 36 100%

A better definition of randomness is that given an infinite amount of trials of random variable \(Y\), we get the true distribution where the outcome of the next realization of said random variable is still unpredictable. So say you are throwing some dice in a casino and you are trying to figure out what is the bet that makes sense where in this odd casino you are meant to bet on the sum of the two dice. The number actually rolled will be a realization (what you actually rolled) of \(Y\) at time \(t\). Any given roll will be unpredictable -- otherwise you could easily bet on it -- but it is deterministic -- i.e. if at the point of the throw you had a lot of time and all the laws of physics you could say with 100% certainty what the roll it is going to be. Yet right now, you do not know. However, that does not mean that it does not follow a certain distribution even though it is unpredictable.

Now there is no doubt that if you come across any given pair of dice and you are asked what do you think the next number will be 7 should be your top choice. (Because it minimizes likely how far off the true number you are likely to be, both because it is in the middle and because it is most likely.) That is what can be thought of as expectation. However, generally the expectation lies in the middle of the distribution, but need not be the most common value. This becomes more obvious if we look at the formula for expectation. It is basically a weighted average of the value (\(y\)) and the frequency (\(f(y)\)). (Where \(a\) and \(b\) are the boundary points.)

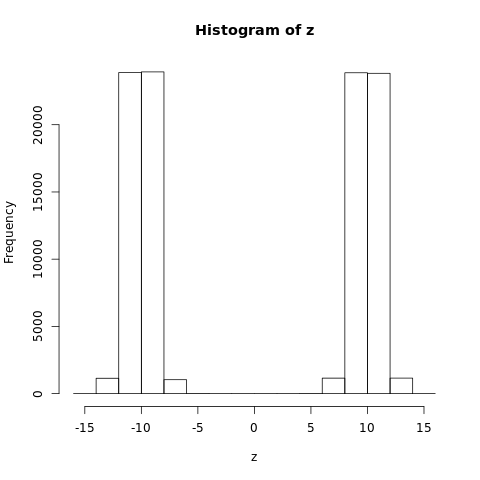

In theory, we can even have a distribution where the expected value is impossible, such as the one below: (for a concrete example imagine student's ratings of a really controversial class on a scale from -15 to +15, where the two groups are equally split and the average rating is about zero)

If you look at the formula for expectation above it is all very nice and mathematical. We have our best guess that makes sense, but is far from guaranteeing that we are actually walk back home with a lot of money. But what if you could observe rolls of two dice would they be perfectly distributed according to the distribution that we have specified? Well, no. Dicemakers probably tried to make them as balanced as possible, but probably every pair of dice has certain numbers that will come less or more commonly than simple combinatorics would suggest. This deviations might be due to tiny imperfections on the table, the dice themselves or many other factors. If you find statistically significant relationships, we might be able to derive a marginally better model. But it is only going to do as well as the strength of relationships. Moreover, if we find these associations and do not really understand why -- e.g. we just observe, they might backfire, because if maybe we found some irregularities on the table and then we start throwing on other parts of the table, we will start losing more. Our model did not generalize "out of sample" (on what we did not observe) well.

Now bring this back to social science. Some people choose to think of the economy as some sort of machine, which suggests determinism. Let's accept that for a second.

Even if we do we have two problems:

- The underlying nature of the system keeps on changing. Sure, economy can be a machine, but it will be a different machine in March 2014 and different in April.

- It does not actually explain why there is any randomness. A machine is deterministic, so shouldn't our predictions be too? It turns out that it is the emergent property (or rather the fact that we have incomplete information) that makes it random. So yes, the world may be deterministic but we need a lot more information that we ever have. Hence we are trying to abstract models that capture the key information. So in our dice example we can notice that the side with one is heavier than the others and hence might come up marginally less often and even though the dice roll is always deterministic, the best heuristic, if we cannot exactly calculate everything, is to use the base rate (how often does 7 naturally occur) plus whatever extra information we may have (heavier sides?).

But randomness only really makes sense if we are actually trying to predict something. We are essentially saying that there is a part that our model (the base rate and extra information together) can predict [1] and a part that our model cannot explain -- i.e. the error term [2]. Basically whenever we don't get our prediction exactly right we get an error -- the difference between actual and expected value. So what we are basically saying is that at this level we can only explain so much and the predicted value is our best guess. That is, after all, what we are doing intuitively with the dice as well: we all intuitively know that predicting always that the outcome is going to be 3 is not a good strategy, unless we know that the dice are biased towards them.

So really, this problem is not unique to social science, but rather inference in general. Because all of the extra information we have probably included in our prediction. Think about predicting rain: to have rain you need clouds, hence if there is a huge black cloud over your head your prediction with this extra information will already be say 90%, but that is only because we have already built the model (we know) that if there's a could over our heads it it is likely to rain. The fact that it does was not a trivial insight at some point. This is what we are doing in science, except with much more difficult concepts. Hence, randomness has to be an emergent property of any predictive model with incomplete information. And since we make predictions so often in every science and the error term has to be random (otherwise we could easily figure out a better model), which is why all the good models of complex behavior have to have a random part. But always keep in mind that the distribution of errors can vary, but there is always going to be a random part by definition unless we know the true model (i.e. we have complete information).

I hope that this was helpful and that you know at least sort of understand why randomness is not a property of human systems, but of prediction with incomplete information and that there are different forms that randomness can put on. But I would love to hear your thoughts and feedback, let me know!

[1] usually denoted as \(E(Y | {\bf X } )\)

[2] usually denoted as \( \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\), though it can be distributed according to a wide variety of distributions.

GANs & applied ML @ ICLR 2019

TL;DR: at the bottom. I have just return

AI Gets Creative Thanks To GANs Innovations

For an Artificial Intelligence (AI) professional, or data scientist, the barrage of AI-marketing can evoke very different feelings than for a general audience. For one thing, the AI indu

List of ICML GAN Papers

In all seriousness, however, I do respect greatly all the amazing work that the researchers at ICML have presented. I would not be capable of anywhere near their level of work so kudos to them

Comments